Forests & Bark Beetles

FORESTS & BARK BEETLES

There is a strong correlation between drought years and bark beetle irruptions. Available soil moisture is the key. Drought and the lack of available soil moisture results in the tree closing its stomata, or gas exchange valves. This reduces water loss through evapotranspiration, But it also reduces turgor, or water pressure in the tree. The reduced water pressure causes the tree to emit a unique pheromone called an ‘aggregating pheromone’. This pheromone, or chemical trail, attracts bark beetles to a stressed tree.

There is an ecological role of bark beetles in the forest. Their role is to create openings and introduce diversity in an otherwise homogenous forest type. These openings introduce a younger age class and break up the continuity of the host’s forest structure. Which is typically one species and one age class. City parks are a good example of this lack of structure and diversity. We want to see large diameter, older trees but they come with a unique set of problems- space, nutrient and water requirements in a limited, artificial environment.

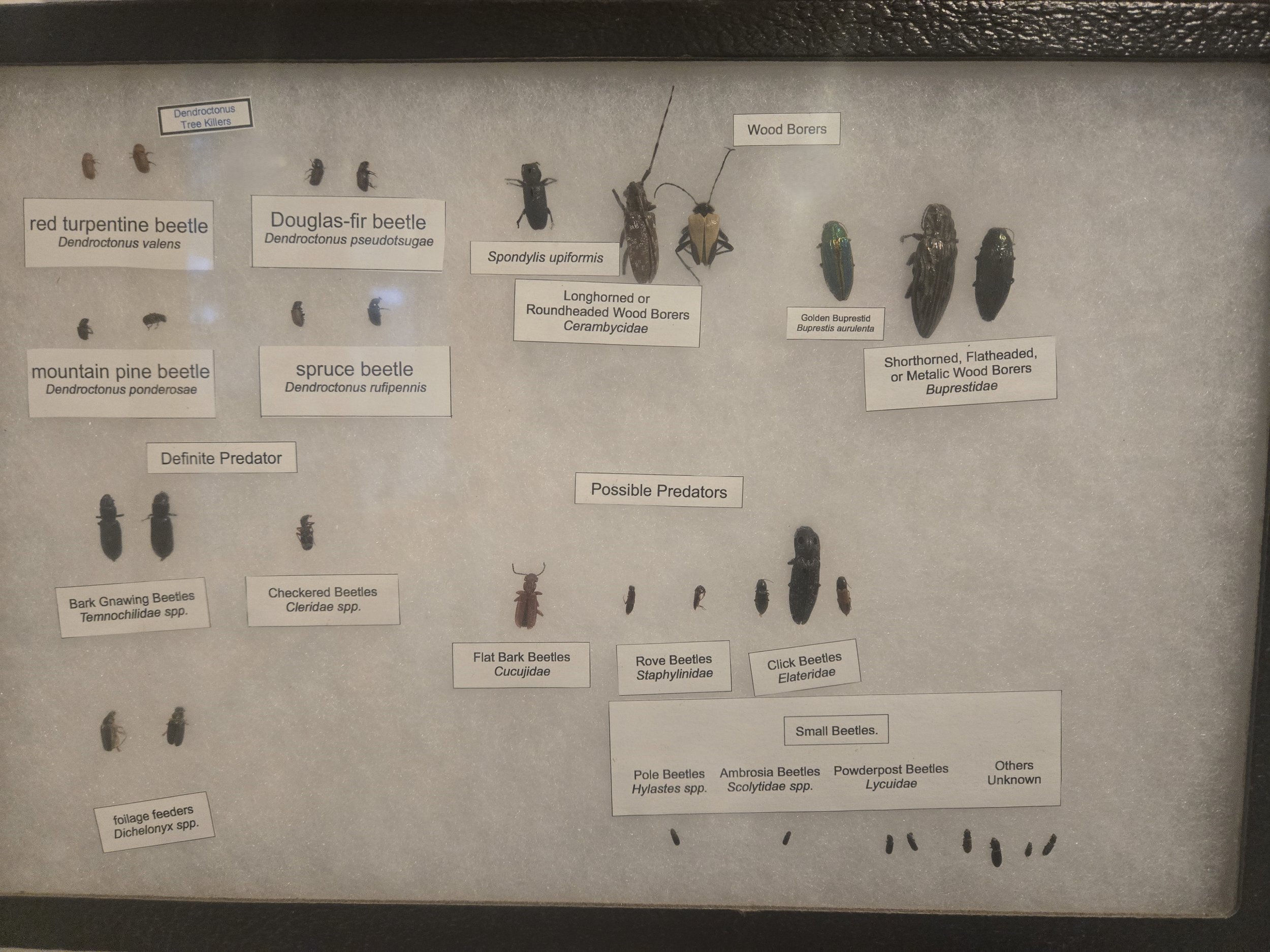

There are several species of bark beetles in our temperate forests. Most are in the genus Dendroctonus. Dendroctonus is a Greek word meaning literally “tree killer”. All tend to be species specific. Douglas-fir beetles (Dendroctonus pseudotsugae) attack Douglas-fir trees and occasionally western larch. Irruptions generally begin in windthrow, storm breakage, log decks, and older trees often associated with root disease. Mountain pine beetle (D. ponderosae) typically attacks lodgepole pine. However, it has evolved and will infest young pole sized ponderosa pine because its primary host has been previously decimated by this species. Red turpentine beetle (D. valens) attacks larger diameter ponderosa pine near the tree’s base. The tree, over time, has adapted a unique defense mechanism. It isolates the beetle in a resinous cavity near its entry point. This beetle seldom kills the tree. Though it may weaken it enough to allow other beetle species to invade the tree. Western pine beetle (D. brevicomis) is a relatively small bark beetle species but is the most damaging. While most bark beetle species overwinter in the surface soil layer and duff, the larvae for western pine beetle overwinters under the bark typically in the mid-portion of the tree. Woodpeckers and flickers will peck the bark of the tree and feed on the larvae. It is easy to identify a western pine beetle outbreak in the winter, especially since the tree will be stripped of its bark in the mid and upper portion of the stem. The fourth bark beetle common locally is the slash beetle (Ips pini). It attacks smaller trees in over-crowded stands as well as unmanaged logging slash and slash piles, hence the name ‘slash beetle’. The spruce beetle (D. rufipennis) will attack Englemann, Sitka, and Brewer spruce trees typically larger than 12 inches in diameter at breast height. Jeffrey pine beetle (D. jeffreyi) will attack and kill Jeffrey pine and usually in the larger diameters only. Higher elevation forests are not immune to bark beetles, either. The fir engraver (Scolytus ventralis) is common in the true fir types. It is usually associated with other mortality vectors like drought, root disease, and defoliation events. Silver fir (Pseudohylesinus sericeus) and the fir root bark beetles (P. granulatus) are common in the true fir types and are generally considered secondary agents. They are typically associated with root diseases as the primary mortality agent. The Douglas-fir pole beetle (Pseudohylesinus nebulosus) kills smaller Douglas-fir trees and the tops of larger Douglas-fir that are under stress and are most evident during drought periods.

There are several treatments that offer effective deterrents to bark beetle irruptions. Bark beetles are telling forest and park managers that there is too many trees chasing too little moisture. So the solution is apparent. We increase the moisture with more watering in a park environment or we reduce the number of trees demanding water with a silviculture application and ‘thin from below’ prescription to remove at last a portion of the moisture stress related to overstocking in a forest environment as well as a park environment, too. Stocking in all age classes is a common problem in temperate forests. Early stand treatments are critical. And with a warming and drying climate, it is increasingly important to get early stand treatments done early in the trees growth cycle so the reserved trees have an opportunity to develop root systems and stem diameters adequate to survive more extreme weather events. ‘Thinning from below’ prescription leaves dominant trees with dominant root structures. Periodic prescribed fire in appropriate forest types reduces the duff layer and removes the over-wintering habitat for most species of bark beetles.

While there are aggregating pheromones to attract primarily female bark beetles in over-whelming numbers to these drought stressed trees, there is also a disaggregating pheromone emitted by bark beetles ‘telling’ any additional bark beetles to ‘stay away, this tree is populated’. All bark beetle species require the water available in the cambial layer of the tree to complete their life cycle. So once the tree is populated to a mortality level, the beetles will emit this ‘disaggregating pheromone. The artificial product of this disaggregating pheromone for pine species is called Verbenone. So in addition to silviculture treatments, a second bark beetle treatment is a Verbenone packet dispersal. This treatment may be ideal in an urban as well as a natural forest environment because it makes it possible to save individual trees or groups of trees with proper placement and number of verbenone packets.

One of the challenges in a forest environment setting is how to create and maintain a more complete ecosystem. A typical natural forest contains down, woody material and standing dead. These essential components provide habitat and nesting sites for bird species that often feed on bark beetles and their larvae. The Hairy woodpecker is a significant predator of bark beetles and their larvae. This species usually nests in broken, dead trees. Also, nuthatches and chickadees will graze up and down the bark of infected trees in search of beetles and larvae.

Trapping with pheromones unique to each beetle species is a critical tool necessary to monitor and manage bark beetle populations. Cleaning the traps each week and counting and recording the different beetle species a great tool to determine predator/ prey relationships and whether the beetle population is building or declining.

There are several take-home messages from this document. Firstly, stay on top of mortality. Salvage breakage and blowdown within two months of episode. Secondly, apply appropriate silviculture treatments, particularly ‘thin from below’ treatment to reduce moisture stress on the residual trees. Thirdly, implement a pheromone trapping program to monitor populations. Fourthly, reserve standing broken trees to provide nesting and forage habitat for insect-eating birds that feed on bark beetles and larvae. And lastly, use the disaggregating pheromone Verbenone to defend the broken stem- the snag from beetle attack.

Bark beetle and in fact, most forest treatments are best done pro-actively, before they become a much more extensive and intensive issue resulting in crisis management.

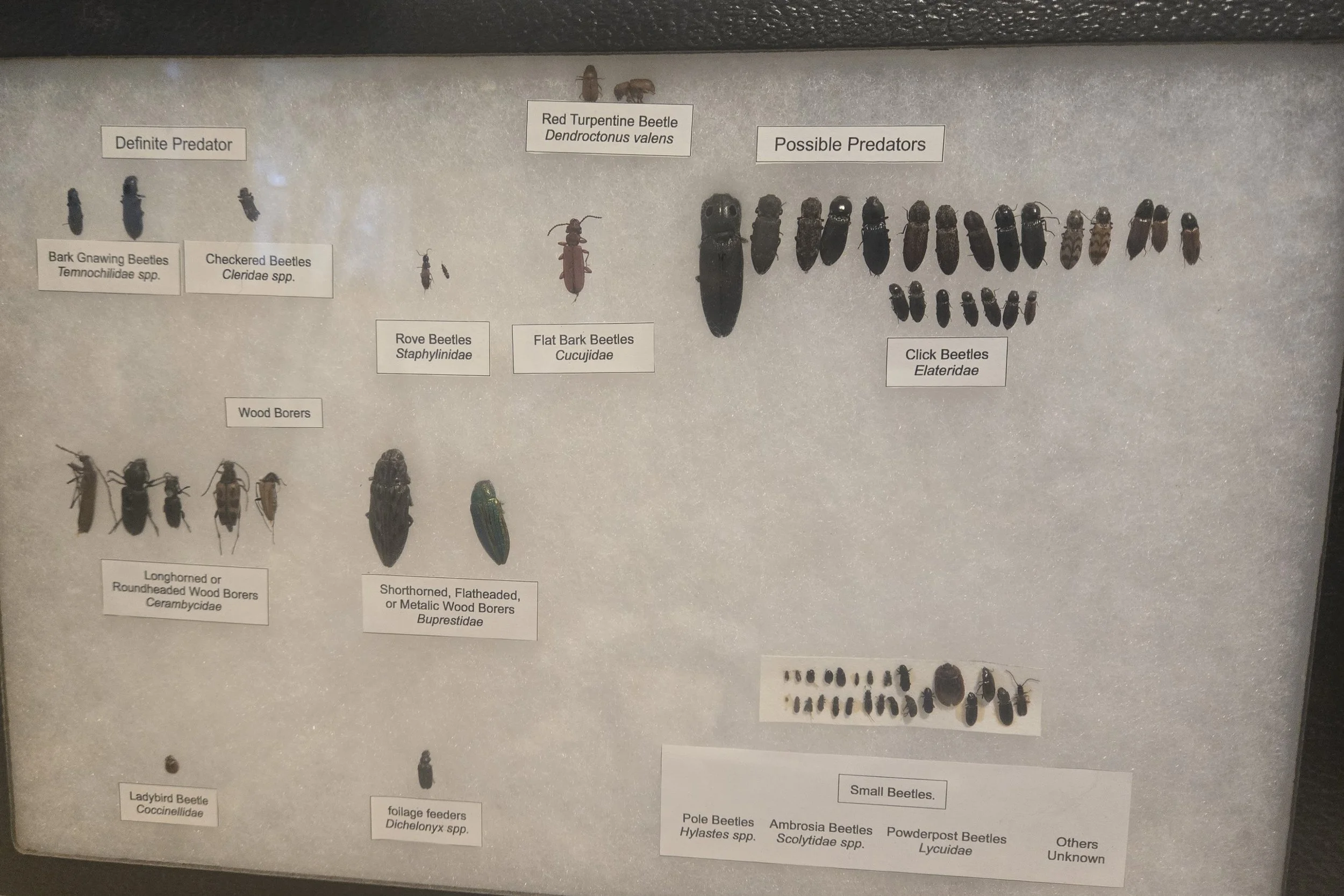

The following insect mounts display the variety and diversity of insect populations moving through the bark beetle ecosystem in a temperate forest environment.